Seeing Is Believing: The Benefits of Ultrasound for Patients and Providers

Understanding “Blood Flow” on Doppler: What the colors and waveforms actually mean

Understanding “Blood Flow” on Doppler: What the colors and waveforms actually mean

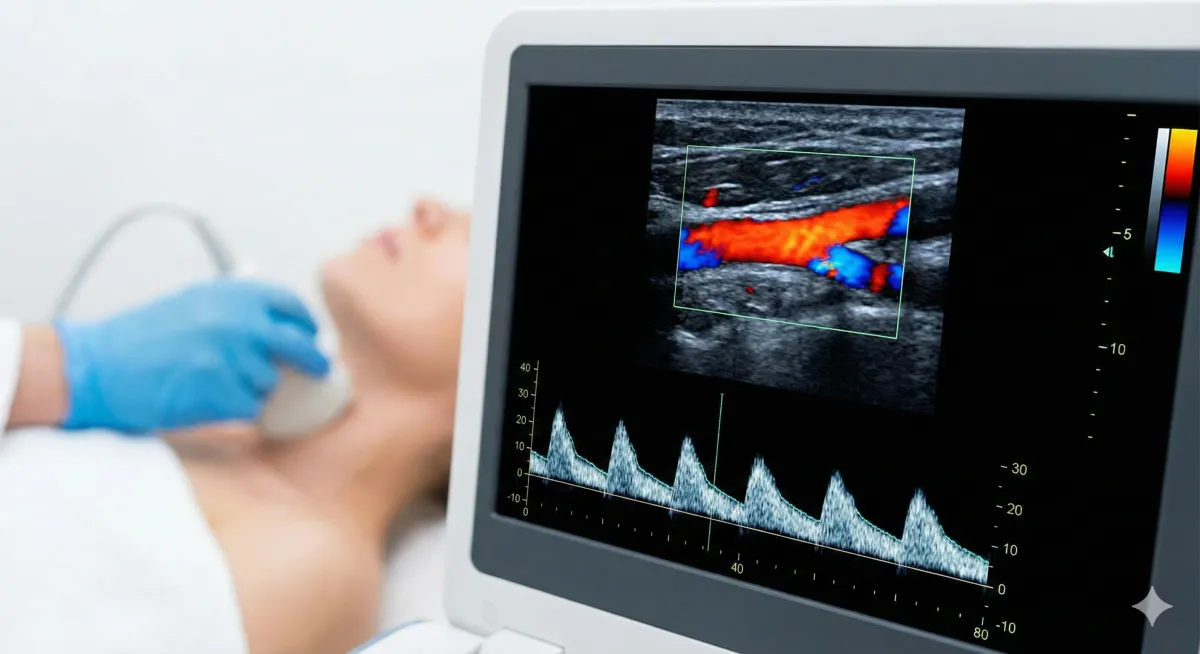

If you’ve ever looked at an ultrasound image and thought, “Why is everything suddenly red and blue… and why does it look like a tiny weather radar?”, you’re not alone.

Doppler ultrasound is the part of ultrasound that estimates motion—most commonly blood moving through vessels—by listening to how returning sound waves change when they bounce off moving blood cells (the “Doppler effect”). The machine then translates that motion into colors and/or waveforms that clinicians can interpret.

This post will help you read what you’re seeing without falling into the most common trap: assuming the colors mean “good vs bad” or “oxygen-rich vs oxygen-poor.” They don’t.

The big idea: Doppler shows motion, not “health” by itself

Doppler tools answer questions like:

Is blood moving toward or away from the probe?

How fast is it moving?

Is the flow smooth (laminar) or chaotic (turbulent)?

How does the flow change across the heartbeat?

Those answers become useful only when a trained clinician interprets them in context (what vessel, what patient, what gestational age, what symptoms, what other measurements).

Part 1: What the Doppler colors mean (Color Doppler)

1) Red and blue are about direction relative to the probe

By convention, most systems display:

Red = flow toward the transducer (probe)

Blue = flow away from the transducer

This is a convention used broadly in ultrasound education (often remembered as BART: Blue Away, Red Toward).

Important twist: the operator can invert the color map. So red/blue can be swapped depending on settings.

2) Lighter/brighter shades usually mean faster flow

On many systems, brighter red or brighter blue indicates higher velocity (faster movement).

3) The color bar is the legend (don’t ignore it)

Somewhere on the screen you’ll usually see a color scale with a range of velocities. That scale is how you decode what “bright” actually means on that exam.

4) The colors do NOT mean oxygen levels

This is the most common misconception. Doppler colors are not like “red blood / blue blood.” They’re direction + speed, not oxygenation.

Part 2: Why the colors sometimes look “mosaic”

Sometimes you’ll see a patchwork of multiple colors in one area. Two common reasons:

1) Aliasing: “too fast for the setting”

Color Doppler has a speed limit (based on the chosen scale). If blood is moving faster than the system can display at that setting, it “wraps around” the scale and can flip colors abruptly. Clinicians often adjust the scale (PRF), baseline, and other settings to manage this.

2) Turbulence: messy flow

When flow is disturbed (like downstream of a narrowing or around a sharp turn), velocities vary within the same small region—so you can see a speckled, chaotic look.

Bottom line: mosaic ≠ automatically dangerous. It’s a clue that prompts the operator to optimize settings and interpret carefully.

Part 3: What the “waveform” means (Spectral Doppler)

Color Doppler is the “map.” Spectral Doppler is the “graph.”

How to read the graph

A typical spectral Doppler display plots:

Time across the bottom (left → right)

Velocity on the vertical axis (how fast blood is moving)

A baseline in the middle

If the waveform is above the baseline, flow is in one direction; below the baseline, it’s the opposite direction (again, relative to the probe and settings).

Why waveforms look spiky

Arteries carry blood pushed by the heart, so arterial waveforms tend to be pulsatile:

a tall peak during heart contraction (systole)

lower flow between beats (diastole)

Veins usually have lower-pressure, steadier flow patterns (often influenced more by breathing and nearby pressure changes).

Part 4: The common measurements clinicians extract from waveforms

You may hear or see indices like RI or PI. These are not “magic numbers,” but they help describe how resistant the downstream vascular bed is.

Resistive Index (RI)

A common definition is:

RI = (Peak systolic velocity − End diastolic velocity) / Peak systolic velocity

Clinicians use RI (and similar indices) as one piece of evidence about flow resistance—always interpreted in context.

Pulsatility Index (PI)

PI is another flow-resistance-related measure used in many clinical contexts (especially where pulsatile flow matters).

If you’re a patient reading a report: don’t try to “grade” yourself using these numbers. A value that’s normal in one vessel (or at one stage of pregnancy) may be abnormal in another.

Part 5: Why Doppler results can vary (even when nothing is wrong)

Doppler is sensitive to technique. A few big reasons readings can differ:

Angle matters: Doppler estimates velocity best when the beam angle is appropriate; poor angles can distort numbers.

Settings matter: gain, scale, filters, and sampling location can change the display a lot.

Safety note (especially in early pregnancy)

Doppler modes (especially spectral Doppler) can involve higher acoustic output than basic imaging modes, so professional bodies emphasize prudent use and following the ALARA principle (“as low as reasonably achievable”) use the lowest output and shortest time needed for clinically useful information.

ISUOG’s safety statement also emphasizes that Doppler should not be used routinely in the embryonic period unless clinically indicated, and that operators should pay attention to safety indices like TI (thermal index) and MI (mechanical index).

(For patients: this isn’t a reason to panic. It’s a reason to trust trained clinicians who use Doppler appropriately.)

Quick myth-busting (because the internet loves chaos)

Myth: “Red means artery, blue means vein.”

Reality: Red/blue = direction relative to the probe, not vessel type.Myth: “Blue means low oxygen.”

Reality: Doppler doesn’t show oxygenation.Myth: “A messy color pattern means something is definitely wrong.”

Reality: Could be aliasing, settings, angle, or turbulence—interpretation needs context.

The takeaway

Color Doppler is a direction-and-speed map. Spectral Doppler is a speed-over-time graph. Both are tools that help clinicians evaluate circulation—but neither is meant for DIY diagnosis.

If you ever want to sound like you know what you’re looking at (without fooling yourself), remember:

Check the color bar. Ask what vessel it is. Ask what question Doppler is being used to answer. Everything else is noise dressed up as certainty.